Principia de Humana Naturali:

- Xuelong An Wang

- Apr 20, 2020

- 13 min read

a critical examination of a fundamental framework to encapsulate the theories concerning human cognition and behaviour

Abstract: The following paper attempts to provide a basic unifying theoretical framework capable of encapsulating the diverse theories concerning human cognition and behaviour, which is done with the purpose of gearing the study of philosophy in the present and the future in a coherent and cohesive manner. Such framework will be argued to be survivability, the notion that the human being seeks to maintain its own existence inside its immediate environment. Section I lays out the implications of such framework and elaborates on how this concept permeates into the different faculties the human being, simultaneously defending how it can support diverse theories regarding cognition and behaviour. Section II explores the role of uncertainty in shaping such framework. Finally, Section III concludes with the ultimate acknowledgement of the opaqueness of human nature, stating the impossibility to draw an accurate description (or definition) for such, hence leaving an open discussion regarding what’s pushed forward in this text. It’s worth mentioning that this paper is not to be taken as an assertion of what lies underneath of cognition and behaviour, nor a redefinition or critical examination of the theories behind them, in other words, it’s not seeking to unpack any mentioned theory. Instead, it envelops them through the concept of survivability, uncertainty and opaqueness as a way of finding a unifying and underlying basis for them.

Keywords: survivability, uncertainty, opaqueness, fundamental framework, principles, human nature, cognition, behaviour.

Section I: The need of survivability

For more than centuries, humans have attempted to dissect the mysteries lingering behind of what today is known as cognition, behaviour, emotion, perception, among others. This began with lively debates among philosophers regarding how and why humans gain and process knowledge, i.e., the dichotomy between nativism and empiricism[1]. Until the recent decades, this discussion evolved into a systematic field of study and some may call it as the “Science of Intelligence”, attracting researches from very diverse backgrounds ranging from cognitive scientists, psychologists who use such results to understand the human body and be able to cure diseases or enhance memory’s performance, economists who use their findings to find ways to influence human behaviour during decision making, computer scientists who pursue the making of more intelligent agents, among others.

However, what began as a field of study that requires the cooperation between distinct fields became one that ramifies itself into different branches, with each one growing by itself not necessarily at similar rates (see Núñez et al., 2019). This incoherence in research, the lack of mutual understanding and cooperation among the distinct fields, may pose a challenge for a cohesive development for studying cognition, hence the need for unifying frameworks have been laid upon, and attempts have been successfully made (see Clark, 2013).

Just as how the study of physics found its rise by accommodating everything to fundamental aspects such as fields, matter and energy and their interaction, the philosophical study of the constituents of human nature can search for a unifying basis that can help gear its own future research and establish a steady, coherent development. In other words, what are the equivalents of fields, matter and energy in the field of human nature?

Survivability as the energy for running prediction machines

Human nature, though undefinable, can be described as an amalgamation of the distinct faculties of humans, such as perception, cognition, memory, behaviour, language and emotion. The following text attempts to draw connections between survivability to some of those faculties.

To begin, a novel and very convincing model for human cognition has been the Bayesian brain, advocating for a multilayer generative model aimed at constantly making and processing predictions and minimizing errors from such (see Clark, 2013). This has been a rather revolutionary way of viewing cognition as it established a dividing line from traditional ways of addressing the human brain as a massive storage of data and algorithms. It invites the notion of treating the human being not as an independent agent, but rather an embodied animal that’s capable of coping with the challenges posed by the immediate environment it lives in, ensuring its survival by having a representation of its surrounding that’s able to gear its actions.

But, a question may arise: why and how is it useful to have a prediction machine? Why is the model designed to predict while minimizing error and not do something else?

A possible response is that the PP model is the most efficient one in ensuring the survival of the agent. Such fundamental issue of survivability can consist of nourishing the system properly, reducing harm to the body, or cooperating through communication or exploiting tools, among others. For example, if an individual perceives a sandstorm incoming, in order to reduce harm to his eyes his mental structure would parse the elements in his surrounding (clothing, eyeglasses, accessories), predict their functionality and respond to the changing environment by acting (using scarf to cover eyes). Again, this marks a contrast with traditional ways of viewing cognition as a registry of data as it would mean that if the individual hasn’t been exposed to the environment, then he wouldn’t know how to act as there is no previous information regarding how to behave during a sandstorm.

Survivability may have also geared the predictive processing model since it’s designed in a way that’s able to function properly despite poor input. Human beings can perform complex tasks despite having a relative poor amount of input (this is partly due to the natural biologically limits of the eye , given that what acutely detects colour and details is in the fovea centralis, which accounts for about 15° out of 200° of range of vision (R., 2017)). This is by implying that humans, despite not seeing every aspect of nature in detail, instead hierarchically chooses some of them, he can predict the rest of useful features and how they can be used for their benefits. This reduces time of processing, as there is less data, and also makes actions faster[2]. This seems to support survivability as it’s coherent with the notion of maximizing an agent’s functionality even when inputs are either not readily available, or there is the need to discriminate among those inputs in order to cope with certain threat, and not dwelling into a thorough examination of them.

Hence, returning back to the question, representing the world through the PP model aids the agent in enhancing its survival as it’s time efficient and input productive. This becomes more evident through the sharp contrast with other forms of intelligence, mainly artificial intelligence. Despite currently witnessing the great potential that AI shows to the human society, such as the capacity to run complex simulations able to reconstruct time and space, make accurate predictions about certain event that may threaten humans, defeat champions in distinct fields of entertainment, it’s worth noting that by being task-oriented[3], it’s only capable of performing extremely well on the task it was designed to employing ad-hoc parameters. However, humans are survival-oriented, in which along with centuries of evolution and subsequent adaptation to the environment, helped him to able to design such tools at the benefit of them.

Survivability permeating the different fields of human nature

Although survivability can be linked to past ancestors seeking to maintain their existence from the imminent threats posed by the environment, in this paper this doesn’t mean that the survival apparatus remains unchanged and is thought of archaic, but rather a constantly self-innovating apparatus that has upgraded by adapting itself to the contemporary times whilst maintaining the essence of pursuing survival. The way it has adapted can be shown by the distinct biases as shown in the different faculties of humans.

In terms of memory, a faculty that’s useful to store and retrieve from data that’s gathered for the benefit of the agent, it has been repeatedly shown that it’s very prone to forgetting (see Ebbinghaus, 1913 ) and this can be due to several factors, such as aging or disease. However, in addition to that, by adapting the survival apparatus, forgetting can be rethought of not simply losing information, but rather filtering irrelevant data in order to prioritize the few that benefit the most the agent. In other words, it can then be explained on why thoughts that concerns the well-maintenance of the agent are better consolidated over those that are unrelated or have no impact over it, i.e., remembering the names of lifelong partners or colleagues over remembering the design pattern of certain furniture. In addition, those events that pose a threat to the agent are also subject of more attention given that the apparatus may seek to prevent or avoid such scenarios again, which can be referred to the negativity bias. Thus, another possible instance the interplay between the PP model and the survival apparatus is through dreaming. According to Garfield (2001), there appears to be universal or archetypical dreams that people have cross-culturally, such as being chased, falling, appearing naked in public or driving a car without brakes, among others. It can be explained that such phenomenon occurs due to the mind making predictions about the possible scenarios where the agent might be threatened or harmed in certain way, but due to them not actually occurring in real life, some are left forgotten by the time the agent wakes up as a way of filtering irrelevant thoughts.

Apart from retrospective memories, the survival apparatus in conjunction with the PP model helps explain false memories, such as making a reasonable prediction based on previous input data but is ultimately incoherent with reality (see Roediger & McDermott, 1995). Such prediction errors can also be witnessed during court trials where the victim falsely recalls certain aggressor (see British Psychological Society, 2008). These instances of false memory can be explained as a prediction error arisen as a way to reconstruct or logically assign guilt to an imminent threat to one’s survival in order to dispose of it as quick as possible.

Alternatively, practices that enhance memory can be thought of doctrines that accomplish the function of triggering on the survival apparatus in order to stimulate this faculty; examples can include mnemonics that help simplify the data from the environment (condensation means from less information, there is more reasoning and prediction) or maybe exercising in order to improve thinking skills (see Godman, 2014 ), the latter probably due to it simulating the state of rush when seeking survival during ancient times, a trait inherited from humans’ ancestors.

Language is also subject to survivability, mainly by tracing back its purpose and origins (see Tomasello, 2008), which can be simplified as through gestures cooperate and together overcome the challenges of the environment. Indeed, language has provided a very efficient way to recognize and collectively understand this world by assigning words to most things[4], this way able to identify an object (assigning a noun), extract its properties (assigning an adjective in terms of numerosity or quality) and its function (assigning a verb). Hence the capacity of shape-color bounding, figure rotation or morphing, spatial thinking, among others, are just a reflection of the ability to parse the world categorically and then be able to properly exploit its elements with their distintive qualities[5].

There are also biases in language that can be readily explained through survivability. For instance, the whole object assumption (see Quine, 1960), which refers to the tendency for children to associate words they don’t know to whole objects and not parts of it, can be explained as a bias of humans identifying that a threat doesn’t come, for instance, from an animal’s fur, teeth or ears alone, but rather as a whole, i.e. the entire organism, hence it’s more efficient to label them as easy, as simple and as complete as possible.

Another notion that can be supported is the prototype theory, which pushes forward the notion that categories are organized around a prototype. Indeed, this way, there will be no need to distinguish different objects based on very small or insignificant differences, as it might require a lot of unnecessary examination and subtle yet irrelevant categorization. The ability to generalize can be derived from such, and is a trait of humans that allows them to recognize and classify objects despite being novel for them in a reasonable way. In this way, it doesn’t matter whether a tiger is not of an average size, has a different fur colour or lacks minor features such as a leg, an ear or its whiskers, it’ll still be recognized as a tiger.

There are also biases in decision-making theories, such as the ambiguity effect, which advocates for the preference of an outcome-known option over an unknown one; this can be justified by the pursuit of a sense of security and certainty from the apparatus. When a threat can’t be correctly identified nor consequences be accurately measured, then naturally one would either display a desire to avoid such uncertain scenario or express disappointment for possible losses.

All in all, distinct aspects of human nature are interdependent and constitute biological chain that doesn’t stop functioning. Survivability, hence, is its fuel.

Section II: Uncertainty as the field surrounding human nature

Just as how arbitrariness defined today’s language or the mathematical axioms we use today to study this world, randomness also permeates itself into human nature. Uncertainty is perhaps also another pillar that governs it, and it could be the result of the fundamental probabilistic nature of the human world[6]. Questions such as is the PP model present in everybody and is the structure the same for everyone or why do humans expose certain biases while others don’t, can easily become points of heated discussion. Although a response can be given, such answers must take into account the distinctive and unique natures of each human being, which directly influences how each one thinks and behaves.

From this, it can be extrapolated that the survival apparatus may share the same principle for everyone (to survive), but expresses itself in different ways depending on the agent (how to survive). In that regard, it is possible that this apparatus may have become dull for some, which may result in the lack of pursuit of survival (e.g. falling into a detrimental addiction despite knowing its consequences), while become intense for others. Behaviour, then, can be a reflection of such distinctiveness, which may be perhaps the main factor why it’s impossible to envelop it in a generic theory. Uncertainty, or the acknowledgment that human nature is undefinable, then becomes an adequate descriptor for it.

One cannot generalize ideas in the field of human nature given that because each agent was born differently, its innate features may have been established just randomly too, hence the way it perceives and interacts the world may differ completely from one another. For instance, any reader can have complete different interpretations regarding either Piaget’s genetic epistemology, Chomsky’s Universal Grammar, Hawking’s imaginary time or Clark’s extended mind, which more or less perhaps applies to most ideas advocated by any other person.

Section III: Opaqueness is the matter at hand

Genetic epistemologist Piaget once said that on the study of beginning, there is just no absolute beginning. Slightly adapting from such idea, when trying to seek for a unifying theoretical framework, it’s impossible to find a concrete base. Indeed, the subtle irony is that the more one attempts to dive into these constituents of human nature, the more “bottomless” becomes the abysm.

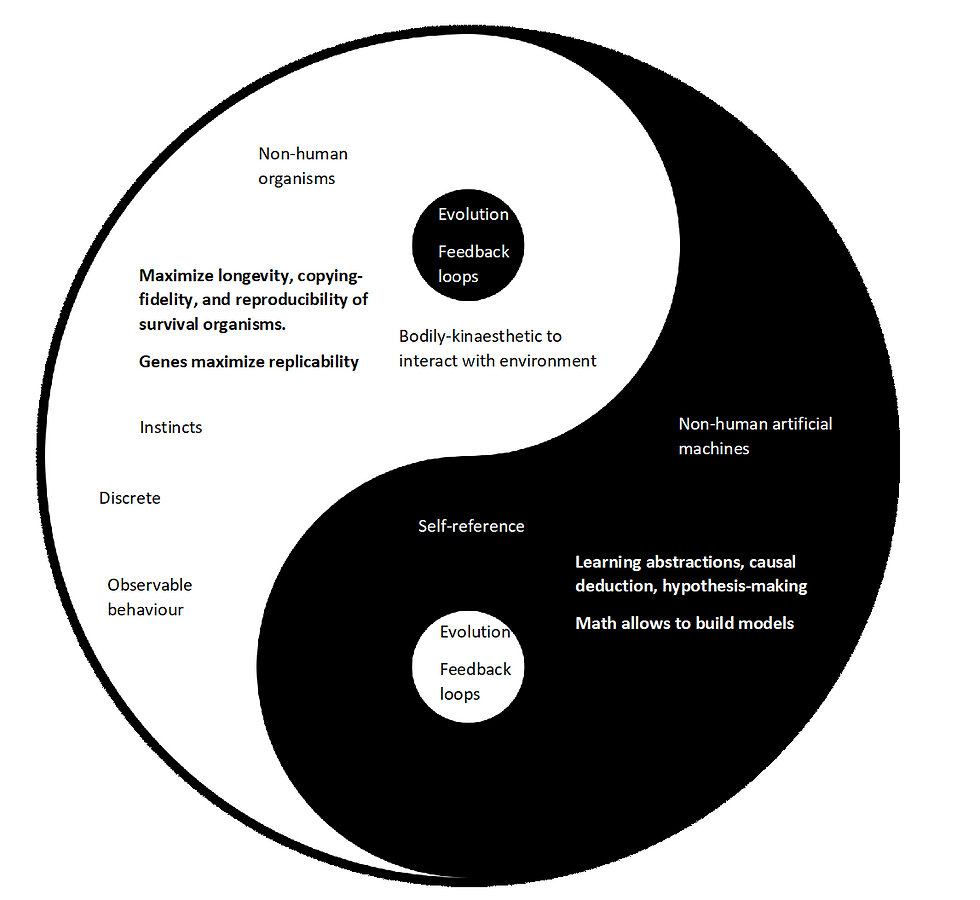

As said above, human nature is undefinable, therefore can only be described. Similarly, though it has been provided several instances of how survivability might be acting as an underlying fuel gearing several human faculties, what’s advocated is the result of interpretations from studies rather than physical evidence; in that regard, this might trigger confirmation bias for those who try to visualize it. Also, because it’s an abstract concept in human beings, it’s also difficult to falsify, as attempts to do so may be justified as reasonable “errors” commited by the model. As such, it’d be impertinent to suggest that there is an accurate way to depict this innate apparatus , but abstain oneself to describe how it influences human faculties (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: a possible depiction of the opaqueness of the human mind

Conclusion

Despite the attempt made to provide an unifying framework for the study of human nature, it’s evident that it came with several issues. Survivability, as an innate feature of human being, then can be left not only as a notion put forward in this paper, but rather a point of discussion judging whether it’s suitable to act as a basis to envelop the different theories regarding the different faculties of human nature. From it, what’s asked to the reader can be the following:

What is survivability for the reader? And which aspects of the reader’s life can be explained through it?

Bibliography

Anderson, F. (kein Datum). Memory and Complex Learning Lab. Von Prospective Memory: https://sites.wustl.edu/memoryandcomplexlearning/prospective-memory/ abgerufen

British Psychological Society. (2008). Guidelines from British Psychological Society on the reliability of witness memory in court. Von British Psychological Society: https://www.bondsolon.com/media/12410/bpsmemorylaw.pdf abgerufen

Chomsky, N., & Schützenberger, M. P. (2000). The Algebraic Theory of Context-Free Languages. In L. Beklemishev, Computer Programming and Formal Systems, Volume 35 (S. 119-123). Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company.

Clark, A. (1997). Being There: Putting Brain, Body and World Together Again. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Clark, A. (2013). Whatever next? Predictive brains,situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES, 1-7, 20-21.

Ebbinghaus, H. (1913). Memory; a contribution to experimental psychology. New York : New York city, Teachers college, Columbia university.

Garfield, P. (2001). The Universal Dream Key. New York: Cliff Street Books.

Giovanni, M. (2017). Capturing interactive alignment with the predictive processing framework. Semantic Scholar.

Godman, H. (09. April 2014). Regular exercise changes the brain to improve memory, thinking skills. Von Harvard Health Publishing: https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/exercise-can-boost-your-memory-and-thinking-skills abgerufen

Goldinger, S. D., Papesh, M. H., Barnhart, A. S., Hansen, W. A., & Hou, M. C. (2016). The poverty of embodied cognition. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, Volume 23, Issue 4, 959–961.

Hawking, S. ( 2001). The Universe in a Nutshell. Great Britain : Bantam.

Loftus, E. F., Miller, D. G., & Burns, H. J. (1978). Semantic integration of verbal information into a visual memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning & Memory, 19–31.

Markie, P. (Fall 2017). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Von Rationalism vs. Empiricism: <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2017/entries/rationalism-empiricism/> abgerufen

Núñez, R. A.-D. (June 2019). What happened to cognitive science? Von Nature Human Behaviour: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0626-2 abgerufen

Paul, M. (19. September 2012). Your Memory is like the Telephone Game. Von NORTHWESTERN NOW: https://news.northwestern.edu/stories/2012/09/your-memory-is-like-the-telephone-game abgerufen

Piaget, J. (1970). Principles of Genetic Epistemology. Great Britain: T.J.I. Digital, Padstow.

Quine, W. V. (1960). Word and Object. Cambridge, Massachusetts : MIT Press.

R., N. (2017). The Fovea Centralis. Von HyperPhysics: http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/vision/retina.html abgerufen

Roediger, H. L., & McDermott, K. B. (1995). Creating false memories: Remembering words not presented in lists. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 803–814.

Samet, J. (19. June 2008). The Historical Controversies Surrounding Innateness. Von Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/innateness-history/ abgerufen

Saud Al-rasheed, A. (2015). Categorical perception of color: evidence from secondary category boundary. Psychology research and behavior management, 8, 273–285. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S78348.

Seth, A. (July 2017). Your brain hallucinates your conscious reality. Von TED Ideas worth sharing: https://www.ted.com/talks/anil_seth_your_brain_hallucinates_your_conscious_reality abgerufen

Seth, A. K., & Critchley, H. D. (2013). Extending predictive processing to the body: emotion as interoceptive inference. Behavioral and Brain Sciences Volume 36, Issue 3, 227-228.

Sloman, S. (2005). Causal Models: How People Think about the World and Its Alternatives. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.

Tomasello, M. (2008). Origins of Human Communication. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science, Vol. 211, Issue 4481, pp. 453-458.

Zhu, S.-C. (02. 11 2017). A light discussion of Artificial Intelligence: Current Situation, Purpose, Framework, and Unification | Finding the root of the issue (浅谈人工智能:现状、任务、构架与统一正本清源). Von Untitled: http://www.stat.ucla.edu/~sczhu/Blog_articles/%E6%B5%85%E8%B0%88%E4%BA%BA%E5%B7%A5%E6%99%BA%E8%83%BD.pdf abgerufen

[1] It has upgraded nowadays as both viewpoints interdepend upon each other, but controversy surrounds which aspects of cognition corresponds to which. [2] This seems to suggest that in the past, due to the unavailability of complex and efficient tools to ensure its survival in harsh environments, prehistoric humans were induced to adapt to such conditions where they can maximize functionality despite poor input. [3] This means that if a robot is placed inside a room, it’ll “perform” poorly (or won’t do anything at all) compared to a baby, whose sense of survival might induce him to cry, crawl or look for food. [4] For this paper, I’ll refrain from words that concerns concepts (truth, happiness, abstract), but only words that refer to objects. [5] Once again, such practice of understanding the world in order to ensure survival can be witnessed in other living organisms, albeit to a much lesser complexity, but poses a challenge for the future development of AI. [6] This can also find its roots in the randomness of genetics, from chromosomal crossing over to unexpected but natural mutations.

Comments